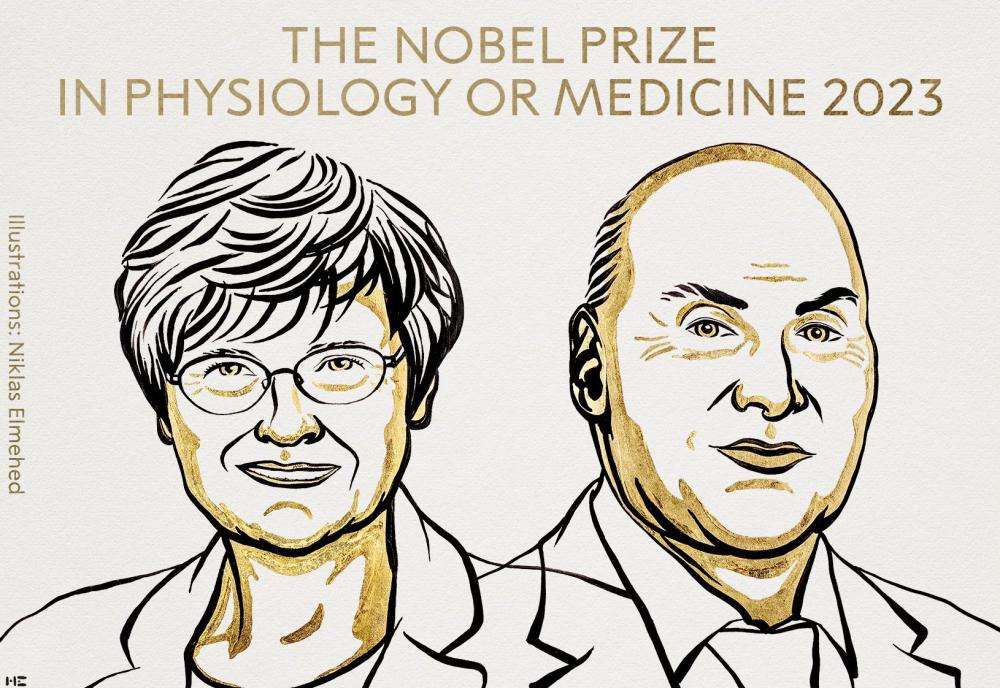

Kathleen Carrico and Drew Weisman are awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their work on RNA technology.

Their work "was crucial to the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 during the pandemic that began in early 2020," the Academy's statement said.

“Through their groundbreaking findings, this year's awardees have fundamentally changed our understanding of how mRNA interacts with our immune system. They have contributed to the unprecedented pace of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health in modern times."

Prizes for Physics, Chemistry, Literature and Peace will follow in the next few days.

American professor Drew Weissman (Drew Weissman) during his award with Katalin Kariko from the government of Japan in April 2022, in Tokyo

This year's Nobel Prizes will be accompanied by a higher prize money, increased by 1 million kroner, bringing the total to 11 million Swedish kroner ($986,000), the Nobel Foundation announced.

Katalin Carrico: From an unknown and marginalized researcher, today a pioneer

Katalin Kariko hugs Tom Hanks on the campus of Harvard University May 25, 2023. Kariko was awarded the title of Doctor of Science while Hanks received an honorary Doctor of Arts.

He was born in Hungary and lives in Pennsylvania. Biochemist researcher Katalin Carrico developed such an obsession with the technology called messenger RNA that it cost her a professorship at a prominent university.

It should be noted that few could have imagined that this method of gene therapy and the persistent work of this biochemist would lay the groundwork for the development of Pfizer/BionTech and Moderna's vaccines against Covid-19.

Somehow, the unknown and marginalized researcher Katalin Kariko is now considered a pioneer.

"It's just unbelievable," she said in December 2020 in an interview with AFP (Agence France-Presse) from her home in Philadelphia. The 65-year-old scientist confesses that it is difficult for her to step into the limelight after so many difficult years in the shadows.

Her case, she says, illustrates "the need to support science at various levels."

Katalin Carrico spent much of her time in the 1990s seeking funding for her research focused on messenger ribonucleic acid (RNA), the molecules that instruct the cell to use, in the form of a genetic code, to produce proteins beneficial for our body.

The biochemist believed that messenger RNA could play a key role in the treatment of certain diseases, such as in the treatment of brain tissue after a stroke.

But the University of Pennsylvania, where Kathleen Carrico was about to take a professorship, put an end to her path, after successive rejections of her research grant applications.

"I was about to be promoted and then just then they demoted me expecting me to leave," he recalls.

At the time, the biochemist did not yet have a U.S. permanent resident green card and needed to find a job to renew her visa. At the same time, she knew that it would be difficult for her to finance her daughter's university studies with her low salary.

Nevertheless, she decided to persevere with her research, despite the difficulty of the undertaking which meant the lack of funding. "I said, the (laboratory) bench is there, I just have to do better experiments."

"Think right and, finally, ask yourself: 'What can I do?' That's how you don't waste your life", is her motto.

This determination, the biochemist has passed on...through her genes: her daughter, Susan Francia, graduated from the prestigious University of Pennsylvania, but also won a gold medal in rowing with the US team at the 2008 Olympics and 2012.

DNA, the most famous big brother

At the end of the 1980s, the scientific community had only eyes for DNA, which they considered potentially capable of transforming cells and, from this point, treating diseases such as cancer or cystic fibrosis.

Katalin Carrico was interested in messenger RNA, imagining that it was capable of giving cells a user manual that would then allow them to make therapeutic proteins. A method that would allow avoiding modification of the genome of cells, modification that would involve the risk of introducing uncontrolled genetic modifications.

and messenger RNA had some problems: it caused severe inflammatory reactions, as it was read as an invasion by the immune system.

Together with her research partner, immunologist Dr. Drew Weissman, Katalin Carrico was able to gradually introduce small modifications to the structure of the RNA, making it more acceptable to the immune system.

Their discovery, published in 2005, caused a sensation and (sort of) brought the researcher out of anonymity.

Then they achieve yet another achievement, succeeding in placing their precious RNA in "lipid nanoparticles", a coating that prevents it from breaking down too quickly and facilitates their entry into cells. The results are published in 2015.

Five years later, at the time of the planet's battle against the coronavirus, these two achievements found their significance.

The two vaccines that were to save the world were based on this strategy, which consists of introducing genetic instructions into the body to trigger the production of a protein identical to the coronavirus protein, which can trigger an immune response.

Catalin Carrico has now occupied an important position in the German laboratory of BioNTech, which, in collaboration with Pfizer, developed the first vaccine available in the Western world. The other vaccine was developed by the company Moderna...its name stands for "Modified RNA".

The pioneer biochemist avoids triumphalism, but retains a bitterness in the memory of the moments when she felt unrecognized: a woman, born abroad in a space dominated by men and where, after the end of certain scientific conferences, she was asked: "Where is your supervisor?" ?”

"They always thought, this woman with the foreign accent, she must have someone behind her, someone more intelligent." Since then, her name was on the list of nominations for the Nobel Prize. As the years passed, her mother became concerned that this had not yet been done.

"I told her: I'm never going to get a federal grant, I'm not somebody, I'm not even a professor!" And to this her mother would reply: "But you work so hard!"